Abstract

This paper analyses SSC as a transformative response to the prevailing climate governance approach from the Global North. From an Eco-Marxist perspective, the study critiques the Global North's epistemic stranglehold, which sidelines localized Indigenous and feminist knowledge, holistically considering the climate. This paper looks into the theory of reparations and demonstrates the lack of responsibility as empty accountability while revealing the captive relationships fostered by the North. The study demonstrates how SSC equips Southern states towards decolonial climate action in South Asia and Africa, framed within justice, equity, and universal epistemologies. This research advocates for grassroots empowerment where women and the Indigenous take charge while calling for the balance of local and transnational regional governance climate governance, creating unity windows. The study proposes a post-capitalist climate framework rooted in degrowth, ecological rights, and resilience, with SSC being the focal point towards climate justice and sustainability.

Keywords

South-South Cooperation, Climate Justice, Eco-Marxism, Global South, Climate Policy, Adaptation, Mitigation, Reparations, Environmental Rights

Introduction

The various aspects of people's lives, including social, economic, and cultural activities, are factors that shape the quality of one's life (Royle, 2020). A more fundamental approach to understanding environmental problems emphasizes the need to incorporate sociological, ethical, and psychological frameworks rather than relying solely on technocratic or economic models. The increasing severity of global climate problems has led governments and international bodies to adopt long-term policies for mitigation and adaptation (Ahmed, 2014). When considering developmental efforts, economic development accompanied by neglect of ecological balance results in a disguised endeavor without genuine intentions to achieve sustainability (Vieira & Alden, 2011).

To modernize their economies, numerous countries in the Global South have attempted to accelerate industrialization; however, this has often had the opposite effect, resulting in deforestation, pollution, biodiversity loss, and resource degradation. Rural depopulation and the decline of farming practices are consequences of infrastructure development, with no prior environmental impact assessments having been conducted. Urban migration has placed an added burden on the already strained city infrastructures, which has worsened ecological imbalances. The need for effective environmental policies is closely tied to international, non-governmental, and local community collaboration at all levels (Weiler et al., 2018).

One significant challenge for effective policy implementation is the lack of integration within global environmental governance systems. Politically, there is cynicism, while administratively, there is infighting that paralyzes any attempts at coordinated action. The South Asian region, in particular, requires international cooperation, as collective action is essential to address climate-related threats. However, such cooperation is challenging due to competing priorities at the national level, as well as the legacy of Northern hegemony in shaping Global South climate policies.

This research aims to enhance the academic climate in the Global South, thereby countering the dominance of Western scholarship and policies. It recommends a cross-comparison of climate governance practices in two Southern countries to highlight local and indigenous frameworks of climate governance. The focus is on tailoring climate responses to transform them into proactive policies that lead to the creation of a positive, decolonized climate policy framework for South Asia, one that embraces the region's socio-political context. The study employs comparative policy frameworks in conjunction with qualitative information to assess climate legislation and its enforcement outcomes across multiple countries.

An in-depth analysis of climate change-related speeches, literature, and policy discourse contains gaps and possible inclusivity narratives. Within this context, reparations are analyzed in the context of climate justice, focusing on the repayment of harmed communities that suffer the brunt of climate-related catastrophes. Reparative justice addresses past injustices and also strengthens the legitimacy of any likely deals to be negotiated with vulnerable states in a climate-focused negotiation framework.

In any case, it is essential to acknowledge that the Global South needs to be increasingly active and proactive stakeholders in the international climate discourse. A case is posited for climate policies constructed from the perspectives of environmental rights, responsibility, and equity. The aim here is to consider climate action not as something that the North spearheads but rather as an initiative grounded in justice and equality emanating from regional solidarity. By fostering policy freedom and horizontal cohesion, Global South countries can transform environmental governance to align with their priorities and lived experiences.

Research Question

This research answers the questions:

Why is there a lack of a unified Southern voice in global climate discourse?

How can the empowerment of Southern voices lead to climate mitigation and climate adaptation and collaboration with Global North over climate action?

The goal of this study is to examine climate policy and discourse with a particular emphasis on South Asia and Africa. The methodology for statistical analysis and content analysis will be used in the research. The goal of this research is to investigate the nexus of climate justice and environmental rights by proposing feasible policy frameworks, examining shortcomings in climate discourse, and investigating the practicality of reparations.

Methodology

Employing a mixed-methods approach that includes content analysis and quantitative data methods, this study conducts an in-depth analysis of the participation of political actors from the Global South (specifically, South Asia) in international climate conversations. The study adds further scope by setting the southern region as a benchmark to assess the efficacy of governance and climate action responsiveness by global South nations in multilateral platforms. The study aims to determine whether the growing political influence of the Global South is effectively leveraged in climate change negotiations and policy development at the international level.

This study also underscores the significance of South-South cooperation in promoting climate action within a specific region. The cooperation mechanism fosters joint environmental concerns and policies while also developing strategies that address the complex challenges faced by developing countries. The work aims to assess climate diplomacy and multinational partnerships in South Asia, attempting to discover how transnational activism can transform fragmented regional interstate relations into a cohesive, collective voice in climate change mitigation discussions. Driven by two central questions, this research aims to understand what southern states do to increase their perceived influence and how much of this influence is gained by presenting forward-looking global narratives on climate change.

This project utilizes quantitative data to assess the performance and impacts of climate policies across South Asia and African countries. By assessing the effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation strategies as well as resource allocation models, the study provides a comparison of policies based on empirical evidence. Such empirical assessment helps capture the impact of emission reduction activities, disaster preparedness, and resource management in countries with comparable development levels. It also provides insight into which strategies have been successful and which ones need to be revisited or further assessed.

Alongside this, qualitative content analysis will be employed to analyze climate-related public messages, crafted statements, and political speeches. Such an analysis is valuable for understanding the narrative frameworks, salient themes, and dominant discourses employed by Southern nations on climate issues. The focus here is on how Northern viewpoints influenced Southern policies and discourses and whether such narratives have undermined or created a space for developing countries' politics in climate negotiations.

Coding themes alongside narrative analysis will reveal the ideologies, power relations, and cultural frameworks operating within the strategies for climate cooperation. With these combined approaches, the study aims to address the critical gap concerning how Global South actors construct narratives of environmental rights and justice and whether those narratives are supported or obstructed by the prevailing governance structures of global governance.

This study provides the most nuanced understanding of international climate politics by employing a mixed-methods strategy. It adds to the scholarship by identifying not only successful models of cooperation and influence but also examining the challenges encountered by underrepresented countries. This study advances the formulation of climate policies that simultaneously uphold social justice and environmental sustainability. With an emphasis on empirical data and discourse analysis, the research aims to strengthen global environmental governance and enable leadership from the developing world in climate justice dialogue, thereby challenging inequitable power structures.

Literature Review

Greater alignment in climate action among countries in the Global South is deeply needed for the successful application of the Paris Agreement and for any meaningful cooperative effort in addressing climate issues globally (Box & Klein, 2015). China, as a key country in the Global South, has been instrumental in promoting South-South climate cooperation through the application of diplomatic policies in renewable energy technologies and lower-carbon development, which have encouraged sustainable pathways in the region (Anderson,, 2008). Such an approach helps address climate change challenges through innovation, financing, and capacity building. The region's politics severely constrain this type of cooperation, as do a lack of financial resources and insufficient infrastructure. These factors limit the effectiveness of collaborative efforts toward climate action (Box & Klein, 2015).

In climate-vulnerable states, civil society is becoming increasingly active as a key stakeholder in shaping policies that address environmental changes. Relatively, these organizations help raise awareness, facilitate information flow, assist vulnerable groups, and provide tangible mitigation and adaptation plans (Burkett, 2006). In Bangladesh and Vietnam, civil society has attempted to mobilize initiatives to ensure that governments are held accountable for incorporating climate policies into developmental plans. In Latin America and South Asia, Climate Action Networks, Sustainability Watch, and other similar organizations have emerged as key players in promoting climate advocacy (Wirsing et al., 2013).

Most NGOs are still confined to operating solely at the national level due to a lack of resources and other institutional challenges, highlighting a particular gap in civil society engagement across different countries. As regions become more politically active and governments become more open, a shift is observed; however, this does not reflect a southern network's attempt to integrate with other actors but rather exemplifies problematic structural issues within the wider governance framework (Smith, 1998).

Compared to the West, numerous countries in the Global South still lack robust legislative and policy frameworks addressing climate issues. Civil networks have been instrumental in highlighting policy implementation gaps and justifying state actions (European Commission, 2020). These groups have undoubtedly shaped structures and policies related to energy access, preparedness for natural disasters, REDD+, and sustainable development. In response to civil society pressure concerning policies that promote environmental justice, countries that were successful in campaigning were offered new laws and administrative bodies designed to aid them (Chaturvedi, 2016).

While civil society activism has registered remarkable successes, it is equally curtailed by insufficient funding, data, and policy-making skills. This shortcoming accrues from neglecting to focus on influential long-term strategic visioning. Nevertheless, their pace-setting efforts—especially in the climate change hotspots—create the enabling conditions for achieving meaningful advocacy work. The advocacy work launches from pilot initiatives, which, when successfully executed, are leveraged to drive legislative change. This bottom-up approach, if documented and systematized, drives sponsorship for state and federal systems (Bhatiya, 2014).

Moreover, attempts to bridge the gap between localized and nationally scoped activism have been successful in changing lawmakers' perceptions of climate change. We have a growing body of evidence that shows these designs are central to triggering legislative action, especially when formulated in conjunction with targeted lobbying and public pressure campaigns. Still, gaps in the civil society networks stem from a flaw in the disconnect between the donors and the community's realities. For many, international funding frameworks appear to favor the dictates of developed nations or global market forces over addressing the issues posed by the vulnerable (Chen, 2017).

The lack of sufficient human and financial resources available within NGOs constrains them to focus primarily on national policy issues rather than region-wide or global initiatives. Nevertheless, the compassion shown by various international funders toward climate-related projects has increased lately. However, the lack of efficient supervision systems often renders such funding ineffective. To improve funding outcomes and ensure accountability, some civil society organizations have begun to demand changes in how funds are allocated and projects are financed (Kennedy, 2017).

These changes often focus on enhancing bottom-up approaches, ensuring alignment with national funding frameworks, and representing traditionally excluded groups. Some advocates have even campaigned against such international ventures, citing their perceived antagonism toward the country's underlying social or environmental focus. The harsh backlash has been directed at projects aimed at supporting carbon trading schemes and those promoting non-developmental financing for national initiatives (Chen, 2017). Civil actors contend that these market-based approaches render political discourse on climate justice a commodified realm where the pollution economy and powerless populations are brutally overshadowed.

The most heated area of contention has been opposition to World Bank projects that are environmentally focused but funded by the World Bank. These projects are allegedly failing to comply with local regulations or causing disproportionate harm to communities. Activists have also called for greater transparency in the funding of these projects as well as in their implementation. There is also motivation for less elitist policies, which increase participation by more diverse sections of the population. This reaction is part of a larger trend of skepticism within the Global South, where externally imposed solutions are countered, particularly when there is little to no Indigenous input. In such cases, the knowledge and dignity of local people are central to the design (Kennedy, 2017).

Eco-Marxism

Environmental degradation during the machine age was marked by massive industrial waste discharge, a legacy that laid the foundation for contemporary environmental crises (Khan, 2021). The rise of environmental political movements, such as the Green Party, has paralleled the growth of global capitalism, which brought environmental concerns to the forefront of political discourse. These parties advocate alternative strategies to confront the existential challenges rooted in unsustainable economic models. Within this context, “ecological Marxism” emerges as a critical framework aiming to confront environmental collapse by reshaping socioeconomic structures through socialist principles (Delinic & Pandey, 2012).

Ecological Marxism, a theoretical branch of Marxist thought, focuses on transitioning from capitalist-induced ecological crises to ecological socialism, particularly in advanced industrial economies. This shift reflects the broader evolution of Western Marxism, which has adapted to modern social and environmental concerns. Proponents argue that ecological Marxism must be integrated into real-world political movements if ecological socialism is to move beyond theory into practice. This integration hinges on two fundamental critiques: overproduction and overconsumption. The former relates to capitalist tendencies to intensify production for profit maximization, often at the expense of natural resources (Warren, 1987). Despite clear evidence of ecological degradation, capitalist systems prioritize short-term economic gains over environmental sustainability due to the profit motive.

Overconsumption, on the other hand, describes the consumer behavior incentivized by capitalism, in which individuals seek satisfaction through the constant acquisition of goods. This unsustainable consumption pattern fuels environmental degradation and amplifies the destructive cycle of production and waste. Both dynamics form the structural backbone of capitalist economies, contributing to resource depletion, pollution, and a deepening ecological crisis (IQAir, 2021). Moreover, ecological Marxists identify the exploitation of developing countries by wealthier nations termed "ecological colonialism" as a practice that deepens global environmental inequality. Advanced nations leverage their economic and technological dominance to extract resources and externalize environmental harms, disproportionately affecting the Global South.

Capitalism’s inability to address these challenges effectively is increasingly viewed as a systemic vulnerability. Ecological Marxists argue that capitalism not only intensifies ecological degradation but also perpetuates Socio-economic inequalities, leaving marginalized populations most exposed to environmental harm (Harribey, 2008). This has fostered a growing belief that environmental concerns are now more urgent than economic growth, pushing for an ideological shift in how global systems prioritize human and ecological well-being (UN News, 2022).

Within this critique, the concept of “alienation consumption” emerges. Scholars argue that modern capitalism promotes artificial consumption as a response to the alienation experienced by individuals engaged in unfulfilling labor (Wirsing et al., 2013). Consumers seek refuge in material goods, falsely believing that increased possessions will enhance satisfaction. This alienation feeds into the cycle of overproduction and environmental destruction. Ecological Marxists call for the elimination of consumer alienation through systemic change, advocating a “zero economic growth” model that emphasizes sustainability, conservation, and fulfillment of human needs over profit maximization (Chaturvedi, 2016).

Conservationism is foundational to this model, promoting production and consumption practices that are ecologically sound and socially equitable. It aims to reorient human desires and production systems to align with ecological limits and community welfare. This includes fostering intellectual enrichment and community empowerment alongside material well-being. Business sectors are urged to fulfill their social responsibilities by supporting sustainable innovation and empowering individuals to pursue meaningful lives within environmental boundaries.

Ecological Marxists propose a decentralized, democratic mode of production as an alternative to the centralized, mechanized systems typical of capitalist economies (Dillard et al., 2012). This shift favors small-scale, community-driven manufacturing over industrial-scale production. Such localized approaches not only reduce environmental damage and carbon emissions but also encourage human creativity and ecological awareness. They argue that large-scale mechanized production, especially in Western countries, reflects an indifference to ecological constraints and serves as a violent imposition on both the environment and human dignity.

The steady-state economy model, which emphasizes limited growth and efficient use of finite resources, aligns well with ecological Marxist principles. This model provides a sustainable alternative to capitalist growth imperatives and ensures long-term environmental and social well-being. By promoting smaller, decentralized production units, this model encourages the reconnection of producers with consumers and communities with their ecosystems. In such systems, workers participate actively in management and decision-making, contributing to personal fulfillment and collective resilience (Delinic & Pandey, 2012).

Ecological Marxists emphasize that globalization intensifies capitalism’s negative ecological and social effects. The global spread of capitalist production accelerates resource extraction and deepens socio-environmental inequities. As natural resources become increasingly scarce and contested, conflicts may intensify. Thus, the ecological crisis is not just an environmental issue but a symptom of deeper systemic contradictions within capitalism (Vieira & Alden, 2011). The proposed solution is not incremental reform but a radical transformation of production systems.

To facilitate this transition, ecological Marxists advocate integrating Marxist principles into ecological movements, enabling them to become effective political forces. This includes connecting ecological activism with wage struggles and class dynamics, thereby expanding the political base of the environmental movement. Additionally, they call for the institutional strengthening of environmental movements so that they can function as organized, influential political actors capable of shaping policy and societal norms. The dual transformation of material systems and ideological frameworks is seen as crucial to achieving a sustainable future (Box & Klein, 2015).

Ecological socialism, as conceptualized by ecological Marxists, represents a mode of production centered on satisfying human needs within ecological limits. It is built on principles of sustainability, resource stewardship, and social justice. The approach aims to address the core issues of capitalist economies: overproduction, waste, and commodification of nature. It envisions a world where production serves collective well-being rather than individual profit, and where natural systems are preserved for future generations (Burkett, 2006). This vision not only critiques the existing system but offers a constructive blueprint for ecological and social regeneration.

Western proponents of ecological Marxism argue that ecological socialism is the only viable path toward liberating both humanity and the natural world from the destructive dynamics of capitalism. They emphasize the need for long-term planning, equitable resource distribution, and democratic control over production. Such a transition would entail systemic changes in energy use, industrial policy, and social values. It would also require global solidarity and cooperation to dismantle the exploitative structures that underpin ecological colonialism.

Africa

Since the turn of the century, the global economy has performed well, but Africa has performed exceptionally well. Despite the fact that the economy is thriving, there is a rising inequality between the affluent and the poor, indicating that the increase in GDP has not been spread evenly. This insight prompted a shift in perspective, emphasizing growth that benefits the poor and reduces inequality over the traditional concentration on GDP. As a result of this revelation, this change in viewpoint occurred. Since its inception, the core notion of inclusive development has been updated and enhanced in a variety of ways. According to Kakwani and Son (2003), after the year 2000, people began to see progress as beneficial to the impoverished. Despite the fact that the concept is still in its early stages, it has already expanded beyond its initial goal of assisting the development of poor persons. Kakwani and Siddiqui (2023) defines "pro-poor growth" as a necessary condition for "inclusive development," and this concept may be further subdivided into "relative pro-poor growth" and "absolute pro-poor growth." Furthermore, "inclusive development" is a prerequisite before "sustainable development" can occur. According to Klasen et al. (2005), a kind of development strategy called "relative pro-poor growth" occurs when non-poor incomes increase at a slower rate than poor incomes. It was determined to develop this novel method of growth. Absolute pro-poor growth is defined as growth that leads to an increase in the absolute incomes of the poor regardless of changes in the earnings of those who are not poor. Ravallion (2020) provided the inspiration for this definition. This definition takes into consideration any changes in the wages of individuals in the middle and upper classes. To put it another way, absolute pro-poor growth prioritizes the rate of absolute income rise for the poor above the degree of inequality. Any form of development plan, whether relative or absolute pro-poor development, should prioritize the position of a society's impoverished people. This should be the end product of both software and hardware development. According to to Klasen et al. (2005), as more individuals participate in the economic progress process, everyone benefits. This is true for individuals as well as society as a whole. One of the distinctive features of inclusive development, according to to Klasen et al. (2005), is the absence of bias and disadvantage. As a result, parallels may be drawn between inclusive development and growth that is disproportionately advantageous to the poor. According to Klasen's (2005) results, inclusive growth reflects changes in inequality more often than relative pro-poor growth. Relative pro-poor growth examines the relative growth and inequality of the poor compared to non-poor people. In recent years, proponents of the concept of inclusive growth have broadened the debate by giving multiple perspectives on the outcomes of development in areas such as education, health, and employment. This was done in order to extend the scope of the discussion. The building and construction industry developed a variety of brand-new and better techniques as a direct consequence of the aforementioned occurrence. Kakwani and Siddiqui (2023) conducted thorough research from the perspectives of several development organizations. To guarantee that everyone has a voice and a stake in development decisionmaking, the Asian Development Bank thinks that gender, ethnicity, race, and the environment should all be included. The World Bank, on the other hand, believes that more vital aims in inclusive development, such as opportunity fairness, social security, and meaningful employment, should take precedence over shortterm income redistribution. The evaluation of the OECD's inclusive development strategy advises abandoning GDP-focused growth strategies in favor of those that emphasize the well-being of all people. This suggestion was made based on the evaluation's results. Based on the evaluation results, this recommendation was developed. The African Development Bank, on the other hand, defines inclusive development as economic growth that increases people's access to improved social and economic opportunities over time. This term may be found in the Manifesto for Inclusive Development of the African Development Bank. The EKC phenomenon has provoked considerable attention and fierce debate among professionals and powerful members of society. The EKC, according to Diao et al. (2009), "may be gaining intense attention and becoming more popular in finance and economic literature than conventional terms such as GDP and prices." According to Diao et al. (2009), the EKC has been cited in several scientific works. The Scopus citation counts provided this information. The proportion of articles including the term "big data" increased by 19%, whereas the percentage of articles containing the words "GDP" and "prices" increased by just 7.8% and 5.2%, respectively. The proportion of all articles that use the term "big data." There is evidence that academic scholars and policymakers are becoming increasingly interested in EKC research. Building on the prior study of Webber and Allen (2010) published the EKC and proposed that after a nation has passed the inflection point, it may "grow out of" environmental decline. They accomplished this by introducing the EKC. This move was performed upon the assumption that nations are capable of "growing out of" environmental degradation. They contend that the rate of environmental degradation in a country accelerates during its formative years of growth, but then levels off once the country reaches a certain level of development. Figure 1 depicts the EKC hypothesis in its most typical form. According to EKC research, the population of developing nations facing substantial poverty chooses economic expansion above environmental protection.

The Environmental Knowledge Center has shown, using the above example, that increased economic success is associated with declining environmental quality. This link has the appearance of an upside-down U. Numerous well-documented researches have been done to determine if the EKC is a theory that may be utilized to anticipate legally enforceable results. There has been much discussion on the subject, but no resolution has been reached. Weber and Sciubba (2018), for example, claimed that the growth in the human population had no negative consequences on the natural environment. William (2005) argue that environmental degradation, such as an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, is a direct effect of economic development. They said that the evidence shows that this method is valid. on the other hand, contended that flaws in the research methods were to blame for the disparities in the findings of these studies. These problems were responsible for the disparities in the results of these investigations. Cederborg et al. (2016) for example, evaluated the relationship between real GDP growth and CO2 emissions per capita in a sample of 15 nations from across the globe. They got some contradictory results in their research on the relationship between the two factors. Despite this, it was discovered that the EKC hypothesis is correct for the great majority of the economies studied. In order to determine whether or not the EKC exists, Onafowora and Owoye (2014) performed research and analyzed data from a range of nations, including Japan, China, South Korea, Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa. Onafowora and Owoye (2014) examined the data obtained from these nations to determine the legitimacy of the EKC. An Nshaped curve was discovered to be a suitable illustration of the time-dependent relationship between economic growth and CO2 emissions. They claimed that the diverse strategies were the consequence of variations in the levels of development existent in different countries.

Asia

The debate over whether climate change is a real phenomenon, a hoax, or a natural event has come to an end. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)'s Fifth and Sixth Annual Assessment Reports give evidence to support this conclusion. South Asia bears the weight of environmental issues and climate change due to the region's high frequency of natural catastrophes (Daily Times, 2022). Increased birth rates in the area will worsen the effects of climate change. The area has a slew of environmental concerns that India and Pakistan are unprepared to confront (Harribey, 2008). Climate change exacerbates the negative effects of factors such as delayed spring precipitation and altered glacier patterns. By the mid-century, an alarmingly huge number of people in South Asia would be hungry. During the 36th meeting of the National Security Committee, Pakistan approved its first National Security Policy (NSP). Within the NSP, there is a significant deal of worry about individual safety. When the final, full version of the NSP is released, politicians and scholars will surely engage in heated discussion (Royle, 2020). The European Commission developed the European Green Deal, a comparable coordinated environmental strategy, in 2020 to help the European Union meet its National Determined Contributions (NDCs) in the same area. Members were expected to make efforts that were both helpful and praiseworthy (Ahmed, 2014). The European Union's ability to collaborate effectively may provide two important lessons. The first is that climate change has no borders, which implies that we cannot fix the world's mounting environmental challenges on our own. Furthermore, the European Union's attempts to combat climate change illustrate that environmental issues affect even the world's wealthiest countries. Non-traditional security issues, such as the threat of natural catastrophes and climate change to almost one billion people in India and Pakistan, are impossible to dismiss today. When seen in this light, climate change may be viewed positively since it offers a chance for India and Pakistan to end hostilities and work to overcome their common environmental issues (Vieira & Alden, 2011). Pakistan and India share environmental problems, which might inspire them to work together to address them. This is without a doubt the most fascinating choice. Ambassador Kaka Khel recently gave a lecture as part of a series arranged by the Institute of Regional Studies (IRS), an Islamabad-based think organization. As he mentioned in his talk, he ascribed environmental difficulties in both India and Pakistan to the precipitate partition of United India in 1947. Climate change affects about 1.5 billion people globally; hence, the repercussions are comparable on both sides of the border. Multiple states working together may be more successful than a single state acting alone. In contrast to present difficulties such as security threats, terrorism, and other socioeconomic catastrophes, persistent environmental issues cannot be remedied by a person or group working in isolation. The Paris Agreement-allocated Global Climate Fund is being disbursed at a glacial pace. It is recommended that India and Pakistan look into alternate financing sources in order to alleviate the current environmental problem or, at the very least, lessen its severity. Since the arrival of the coronavirus in March 2021, the situation has steadily improved. Since the Uri Attack in 2016, hostility has reached an all-time high. Following the March 2019 attacks in Pulwama, India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi met with Pakistani authorities. Pakistan has offered an invitation to India to participate in a bilateral conversation on the unresolved concerns, which include the Kashmir crisis. Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif declared at the 6th Summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Kazakhstan that his country will continue to work with India to safeguard regional peace and security. At this moment, India and Pakistan must work together to avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change, which undermine both countries' security. This kind of partnership has the potential to revive the SAARC regional body while also mitigating the effects of climate change.

Because of the consequences of climate change, environmental concerns are a source of worry for millions of people all over the world. The government's costs and effort spent on these problems are significant. Because India and Pakistan share such a large and porous border, each incident that occurs along it affects both countries equally.

To manage the world's climate changes, we need rules and laws that complement one another. Pakistan and India are under no obligation to quit the IWT. Alternatively, they may use the PIC stage to change the treaty's guiding principles in order to solve the environmental difficulties that both parties face in the Indus Water Basin more efficiently in addition to the issues that occur when water resources are administered across nations, both Pakistan and India have difficulty in managing water resources inside their respective provinces. Rajasthan in India and Punjab in Pakistan each claim a significant piece of the Indus Water Basin. Climate change-induced changes in the IWB may be easier to identify if these two provinces formed a transboundary committee. The settlement of competing interests between Pakistan's and India's different provinces is required for transboundary water management to remain stable.

Because of rising pollution levels, the frequency of dry winters is approaching that of heat waves. Farmers in India and Pakistan routinely burn post-harvest remnants of grass and lucerne to clear land for the next crop. Locals refer to the time when unique flames are lit as "Parali season." The Parali season lasts from the middle of October to the beginning of January. At this time, black smoke is an inconvenience as well as a potentially dangerous situation for people of Northern India and Eastern Pakistan (Weiler et al., 2018). In response to the negative effects of fog, India launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) in 2019. In addition, India abolished the EPCA, an institution in charge of preventing and regulating environmental pollution. The legislation created the Commission for Air Quality Management in the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. In Pakistan, however, government and state bodies lack systems for efficiently monitoring pollution levels. In exchange, India should allow Pakistan access to the commission's earlier efforts and whatever tools it has established. India seeks Pakistan's cooperation to address the impacts and ramifications of pollution. The IQ Air Quality Index named Delhi, India's capital, and Lahore, Pakistan's cultural hub, as two of the three worst cities in the world in December. Smog, as a transboundary environmental concern, needs international cooperation among governments to improve monitoring and alleviate its negative effects.

Because of the region's volatility, even slight temperature swings may have far-reaching consequences in South Asia. Pakistan and India are the countries most vulnerable to climate change hazards globally. According to the Global Climate Index for 2021, natural disasters such as droughts and cyclones have cost Pakistan $4 billion (Box & Klein, 2015). Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif made this point openly during the United Nations' 77th session. He added that, although contributing just 1% to global warming, Pakistan is bearing the brunt of the repercussions (Anderson, 2008). Furthermore, he pushed for developed countries to send climate monies to Pakistan to compensate for the damages and losses caused by climate change. As part of the annual session, Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif met with the presidents of France, Iran, Japan, and Belgium to stress the severity of the 2022 floods and ask cooperation for in the attempt to pay victims. After Pakistan showed strong proof of "loss and damage," the United Nations General Assembly opted to provide cash to address climate change. Throughout the 27th Conference of the Parties, the Secretary-General of the United Nations highlighted the need to put in place strong measures to address loss and damage concerns. This illustrates that countries like Pakistan and India need financial support to make reforms and strengthen their resilience (Burkett, 2006). Although India is one of the main producers of CO2 emissions, the quantity of CO2 emitted per person in India is substantially lower than in nations such as Canada, Qatar, and Australia. India and Pakistan, on the other hand, are both susceptible to the effects of climate change, and the region as a whole needs financial support. Using the SAARC platform, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh may put pressure on the developed world to help the poor world compensate for the destruction and losses caused by climate change.

Data Analysis

The provided text offers a rigorous critique of global climate diplomacy and policy from an eco-Marxist standpoint, highlighting the entrenched asymmetries in North-South relations, particularly as they pertain to environmental justice. Eco-Marxism, a theoretical synthesis of ecological consciousness and Marxist political economy, interrogates the environmental crisis not merely as a scientific or technical problem but as an outcome of capitalist structures and imperialist legacies. This framework allows the critique to unearth the historical and structural roots of environmental injustice and clarify the mechanisms through which the Global North continues to dominate global climate governance.

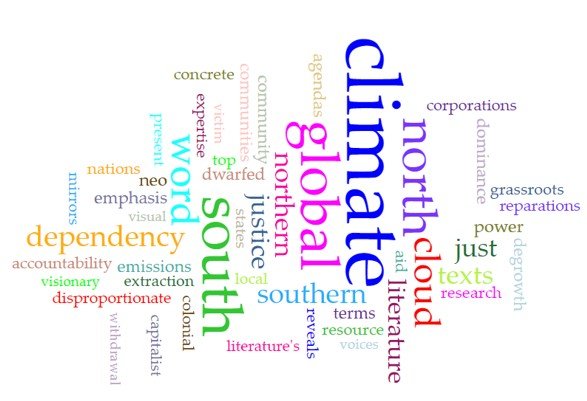

`Figure 1

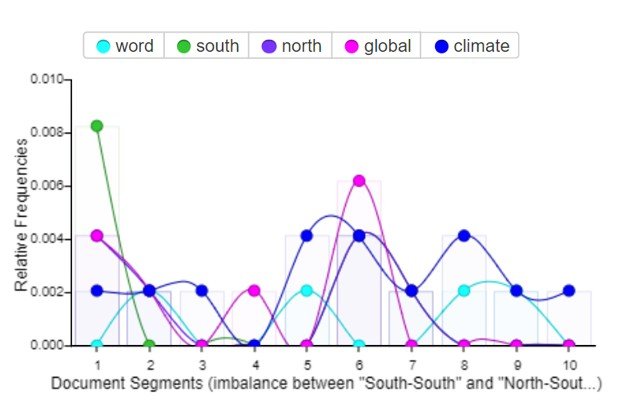

A central theme of the text is the imbalance between “South-South” and “North-South” cooperation, a disparity vividly represented in the word cloud analysis. The dominance of “North-South” over “South-South” cooperation reflects the vertical power structures that still govern climate diplomacy. Within eco-Marxism, this imbalance is interpreted as a continuation of colonial exploitation in a new guise what is often termed “eco-colonialism.” The Global North, through its economic and technological superiority, perpetuates a system of knowledge and policy imposition that silences the Global South.

Figure 2

The text also critiques aid dependency as a mechanism through which this neo-colonial dynamic is maintained. From an eco-Marxist perspective, international aid often operates less as a tool for empowerment and more as a method of coercion. Conditionalities attached to climate aid such as adopting market-friendly reforms or privileging techno-centric solutions—reduce the policy autonomy of Southern nations. This mirrors the broader capitalist practice of creating dependent peripheries to secure markets, resources, and geopolitical loyalty. The research asserts that this mode of governance entrenches inequality and obstructs the radical transformations necessary for climate justice.

One of the most striking observations in the text is the rhetorical presence yet practical absence of “reparations” in climate literature. While the term appears in policy texts, its operationalization remains elusive. Eco-Marxism helps clarify why: the capitalist world order is inherently resistant to accountability, particularly when it undermines the interests of capital accumulation. Corporations and Global North states historical polluters and extractors lack sufficient legal or moral compulsion to compensate for climate harm. The call for reparations, then, must go beyond moral appeals and be embedded in enforceable frameworks rooted in international law and grassroots mobilization.

The discussion around “local” and “communities” versus top-down systemic change offers another valuable intervention. While the literature often celebrates localized adaptation and traditional ecological knowledge, the research cautions against the romanticization of localism. Within an eco-Marxist frame, this critique is essential. Emphasizing small-scale community resilience without addressing global systemic drivers of ecological harm risks victim-blaming and de-politicizing structural injustice. It also allows elites—corporate and state actors alike—to offload responsibility onto communities while continuing unsustainable practices.

The comparison of "degrowth" and "development" in the text sheds light on the discourse surrounding capitalism. There is still an overarching reliance on GDP, technological advancements, and market expansion despite the foreboding ecological crises. Eco-Marxism provides sharp critiques of this phenomenon, exposing rampant social disparity and environmental degradation. The research suggested degrowth as an alternative that challenges the profit-centric society, pursues attainment instead of accumulation, and focuses on people and nature. The literature's disregard for degrowth captures the unwillingness within capitalist societies to accept any challenge to economic orthodoxy. Still, eco-Marxism asserts that without a decisive shift away from growth-centered capitalism, no climate stability is possible.

The 'North' and 'South' word regions pointed in the cloud also greatly strengthen the critique in the mentioned text. The Eco-Marxist theory views this inequality of knowledge as inextricably linked to the South's material subjugation by the North. Disproportionate symbolical power, such as who speaks, whose knowledge is deemed significant, or whose experiences constitute global climate policy, revolves around the Northern climate policy. Who controls policy controls discourse, and therefore, actors in the North can dictate the terms of the agreement, silencing opposing voices? For an equitable and exclusionary climate mitigation regime to form, these dominations must be dismantled.

Like with dependence, this theme is as pivotal. The Global South's dependency on Northern technology, science, and funding cultivates a climate governance architecture that prioritizes compliance over sovereignty. Disciplinary aid, especially in the form of climate finance, reinforces colonial hierarchies. Eco-Marxism critiques this as a form of structural violence, where persistently offered aid reproduces a dependency framework rather than fostering autonomy. The South-South collaboration proposed in the research is therefore radical—not for efficient logistics, but for epistemic and political self-determination.

As contentious as they are, reparations return to the forefront of the issue, and Cotterill identifies them as crucial in the term's broader sense. While it is unquestionable that the South is owed reparations, the research reveals an underlying institutional vacuum in determining how these reparations will be distributed, monitored, and enforced. Eco-Marxism insists that reparations cannot be understood solely in terms of currency but rather as an effort to settle accounts within a broader decolonial campaign that challenges centuries of plundering. This includes restoring resources, implementing sovereign climate policies, and implementing structural changes to the trade and finance markets that are established to maintain inequality.

The removal of grassroots participation, particularly their voices and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), in favor of technical know-how sheds light on the fracture in global policy frameworks when compared to local scenarios. Eco-Marxism argues for the need to democratize the production of knowledge and the incorporation of TEK in the formulation of climate responses. It is concerned with the dominance of technocracy an elite-driven endeavor that further marginalizes the already disenfranchised. Every climate transition framed as 'just' must go beyond shifting fossil fuel emissions to transforming the power relations that determine who is empowered to articulate the issues and who obtains the authority to solve them.

Conclusion

This research conducts an eco-Marxist analysis of the global climate discourse, revealing how Northern epistemic dominance overshadows Southern knowledge, perpetuating neo-colonial domination. It critiqued the "North-South" partnership framework for "cooperation," which deepens the aid dependency syndrome while constraining local realities to technocratic and top-down solutions. The rhetoric of "reparations" lacks fulfillment because there are no enforceable conditions that compel states and companies from the Global North to account for their emissions, depletion, and ecological devastation inflicted in the Southern Hemisphere.

This analysis demonstrates how statist and growth-centric approaches and frameworks tend to suppress grassroots-level mobilization and degrowth alternatives, thereby restricting radical change. It highlights the need for South-South cooperation, which draws upon community-based paradigms such as Buen Vivir, Ubuntu, and Swaraj, which emphasize relationality, sufficiency, and ecological balance. These frameworks resist capitalist logic and offer morally sensible approaches to climate resilience that are grounded in ethnography and juxtaposed with the dominant reasoning.

Advocacy involves establishing new regional working groups for the legal accounting of climate damage, implementing a Global Climate Damages Tax, and setting strict limits on consumption and extraction. Governance must prioritize frontline communities, women, and the indigenous population. Civil society is vital in combating the proliferation of technocratic rule and fostering bottom-up, non-elitist climate policies.

The study proposes integrating agroecology with the democracy of renewable energy as a solidarity economy, in addition to conducting ecological debt audits. Such practices can operationalize reparation strategies through seed banking and stewardship of water by Indigenous Peoples.

References

-

Ahmed, M. (2014). Assessing the costs of climate change and adaptation in South Asia. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/publications/assessing-costs-climate-change-and-adaptation-south-asia

-

Anderson, K. B. (2008). Unilinearism and multilinearism in Marx’s thought. In Proceedings of the XXII World Congress of Philosophy (pp. 13–19). https://doi.org/10.5840/wcp2220085065

-

Bhatiya, N. (2014, April 22). Why South Asia is so vulnerable to climate change. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/04/22/why-south-asia-is-so-vulnerable-to-climate-change/

-

Box, J., & Klein, N. (2015, November 18). Why a climate deal is the best hope for peace. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-a-climate-deal-is-the-best-hope-for-peace

-

Burkett, P. (2006). Marxism and ecological economics. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047408567

-

Chaturvedi, S. (2016). The Development Compact. International Studies, 53(1), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881717705927

-

Cederborg, J., Snöbohm, S., Mentor, & Blomskog, S. (2016). Is there a relationship between economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions? https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1076315/FULLTEXT01.pdf

-

Chen, X. (2017). Marxism and the construction of an ecological civilization. In BRILL eBooks (pp. 427–438). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004356009_021

-

Daily Times. (2022, December 10). UN reiterates support for Pakistan, seeks more funds to fight climate change. Daily Times. https://dailytimes.com.pk/1009274/un-reiterates-support-for-pakistan-seeksmore-funds-to-fight-climate-change/

-

Delinic, T., & Pandey, N. N. (2012). Regional environmental issues: Water and disaster management. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

-

Diao, X. D., Zeng, S. X., Tam, C. M., & Tam, V. W. Y. (2009). EKC analysis for studying economic growth and environmental quality: a case study in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(5), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.09.007

-

Dillard, J. F., Dujon, V., & King, M. C. (2012). Understanding the social dimension of sustainability. Routledge.

-

European Commission. (2020). A European Green Deal. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

-

Harribey, J. (2008). Chapter Ten. Ecological Marxism or Marxian political ecology? In BRILL eBooks (pp. 189–207). https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004145986.i-813.51

-

IQAir. (2021, February 7). Poor air quality in Delhi and Lahore due to crop burning. IQAir. https://www.iqair.com/newsroom/poor-air-quality-delhi-lahore-crop-burning

-

Kakwani, N., & Siddiqui, Z. (2023). Shared prosperity characterized by four development goals: pro-poor growth, pro-poor development, inclusive growth, and inclusive development. The Philippine Review of Economics, 60(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.37907/1erp3202d

-

Kakwani, N., & Son, H. H. (2003). Pro-poor Growth: Concepts and Measurement with Country Case Studies (Distinguished Lecture). The Pakistan Development Review, 42(4I), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.30541/v42i4ipp.417-444

-

Kennedy, P. (2017). Marxism, Capital, and Capitalism: From Hegel back to Marx. Critique, 45(4), 443–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03017605.2017.1377924

-

Khan, S. (2021, December 27). NSC approves Pakistan’s first-ever national security policy. DAWN. https://www.dawn.com/news/1666121

-

Klasen, S., Harttgen, K., & Grosse, M. (2005, January 1). Measuring Pro-Poor Growth with Non-Income Indicators. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/45128236_Measuring_Pro-Poor_Growth_with_Non-Income_Indicators

-

Onafowora, O. A., & Owoye, O. (2014). Bounds testing approach to analysis of the environment Kuznets curve hypothesis. Energy Economics, 44, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2014.03.025

-

Ravallion, M. (2020). On the Origins of the Idea of Ending Poverty. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3692164

-

Royle, C. (2020). Ecological Marxism. In Routledge eBooks (pp. 443–450). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315149608-52

-

Smith, M. J. (1998). Ecologism: Towards ecological citizenship. University of Minnesota Press.

-

UN News. (2022, September 23). Flood-ravaged Pakistan’s leader appeals for urgent global support in UN address. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1127791

-

Vieira, M. A., & Alden, C. (2011). India, Brazil, and South Africa (IBSA): South-South Cooperation and the paradox of regional leadership. Global Governance A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 17(4), 507–528. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01704007

-

Warren, K. J. (1987). Feminism and ecology. Environmental Ethics, 9(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics19879113

-

Webber, D. J., & Allen, D. O. (2010). Environmental Kuznets curves: mess or meaning? International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 17(3), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504501003787638

-

Weber, H., & Sciubba, J. D. (2018). The Effect of Population Growth on the Environment: Evidence from European Regions. European Journal of Population, 35(2), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9486-0

-

Weiler, F., Klöck, C., & Dornan, M. (2017). Vulnerability, good governance, or donor interests? The allocation of aid for climate change adaptation. World Development, 104, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.001

-

William, B. (2005). Economic Growth and the Environment: A Review of Theory and Empirics. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, Part B, 1749–1821. https://ideas.repec.org/h/eee/grochp/1-28.html

-

Wirsing, R. G., Stoll, D. C., & Jasparro, C. (2013). Challenge of climate change in Himalayan Asia. In Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks (pp. 19–42). https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137292193_2

Cite this article

-

APA : Qaiser, R. (2023). South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Global International Relations Review, VI(II), 101-115. https://doi.org/10.31703/girr.2023(VI-II).11

-

CHICAGO : Qaiser, Ramsha. 2023. "South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation." Global International Relations Review, VI (II): 101-115 doi: 10.31703/girr.2023(VI-II).11

-

HARVARD : QAISER, R. 2023. South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Global International Relations Review, VI, 101-115.

-

MHRA : Qaiser, Ramsha. 2023. "South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation." Global International Relations Review, VI: 101-115

-

MLA : Qaiser, Ramsha. "South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation." Global International Relations Review, VI.II (2023): 101-115 Print.

-

OXFORD : Qaiser, Ramsha (2023), "South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation", Global International Relations Review, VI (II), 101-115

-

TURABIAN : Qaiser, Ramsha. "South-South Cooperation for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation." Global International Relations Review VI, no. II (2023): 101-115. https://doi.org/10.31703/girr.2023(VI-II).11